The Emperor Has Two Mothers

|

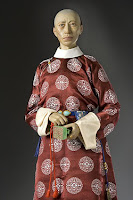

| Emperor Hsien-feng (Xianfeng) |

In 1861 Imperial China was in chaos. Foreign

armies were invading. The Manchu Emperor Hsien-Feng (Xianfeng) was dying. He

and the court had fled north to refuge in Manchuria. His empress Tzu An had

born him no sons. If the Emperor died without an heir, the Ch’ing (Qing)*

dynasty would fly apart. In the winter of 1862 the Emperor died.

|

| Concubine Yehenara, later Tsu Hsi (Cixi) |

Back in 1856 one of his second wives, or concubines, had born him a son! She is known to history as Yehenara. At the last moment, Yehenara, seeing the significance of her situation, forced the dying Emperor to recognize her son as the heir. He did so with his dying breath, and he announced Yehenara as regent for the boy.

However, there was a group of reactionary warmongers, including the dead Emperor’s younger brother Prince Chun (Yixuan), who were preparing to seize the baby emperor so they could control the government. They also planned to do away with Yehenara!

Their plan was foiled when Prince Kung (Gong), the middle

brother, and the smartest of all the line of imperial brothers, arranged to

hurry the widow and little Tung Chih back to Beijing. The funeral procession

bearing the body of the Emperor would shortly follow. Time was of the essence.

Kung quickly gathered support for Tung Chih and his mother Yehenara.

|

| Empress Tzu An (Ci'an ) |

The imperial council was pressured into declaring Yehenara

and Tzu

An Co-Dowager Empresses as well as co-mothers of five-year-old Tung

Chih! They had gained control of the imperial seals before leaving Manchuria,

so the coup d’état had an air of legality.

When the reactionaries (referred to as the “Iron Hats”) arrived

for the funeral, they were confronted by a fait accompli. At the

direction of the wily Prince Kung, the Dowagers issued a decree condemning the

Iron Hats for attempting treason by going against the will of the dead emperor.

With exception of the weak-willed Prince Chun (Yixuan), the ringleaders were

all executed within hours of the decree accusing them. Prince Chun was

easily bullied into complete cooperation with the Dowagers and Prince Kung. The

Dowagers, by the way, were also now joint regents of their “mutual” son Tung

Chih.

|

| Baron Jung-Lu (Ronglu) |

Prince Kung was to remain the principal

manipulator of the central government for many years: he had the support of General Jung Lu (Ronglu), a close

friend of Yehenara, now Tzu Hsi (Cixi). Furthermore, he had the assistance of

the insidious Li Hung Chang (Li Hongzhang). Li was to become the major figure

pulling the strings behind the scenes of the Manchu court for decades to come.

The foreigners loved him, by the way!

|

| Li Hung-Chang (Li Hongzhang) |

While it is true that Tzu Hsi and Tzu An managed to get along most of the time, there is an understanding that there were many contentious moments over the young emperor Tung Chih. One rumor claims that Tzu Hsi played the disciplinarian and occasional punisher, and little Tung Chih would run to his “other” mother Tzu An, who would comfort him and spoil him with treats. Even this lacks credibility, because Prince Kung was the primary dictator of the Emperor’s education and upbringing, not the Dowagers

|

| Tung Chih aka. Tongzhi Emperor |

As Tung Chih grew to his teenage years, he became a willful degenerate just like his father. The Dowagers had to step aside when Tung Chih became sixteen. However, they did help select a wife for him. In 1875, his weakened physique succumbed to disease and he died – apparently childless.

Tzu Hsi was always the more assertive of the two Empress Dowagers.

With the death of her emperor son, she now promoted the succession of her own

nephew. Prince Kung and the council agreed to this, and the two dowagers were

again Co-Dowagers, Co-Mothers, and Co-Regents.

The nephew was just three years old. Tzu Hsi thus embarked on her

second regency. Tzu An was likely bullied into cooperation, as she usually went

along with Prince Kung and Tzu Hsi.

|

| Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi (Cixi) |

It should be pointed out that at the beginning of their joint

rule, the Dowagers were given equally lavish apartments in all royal

residences, equal servants, honors and incomes to go with it! Tzu An was never

belittled or pushed aside. Regardless of how they felt about each other, they

always manifested an air of mutual respect and courtesy. When Tzu An died in

1881, she was accorded all the honors due her – and Tzu Hsi wept, suitably.

All through the 1870s, 80s and 90s, the Empress Dowager Tzu Hsi

gradually became the more assertive of the two women. She was pushed forward by

Prince Kung, and later by Li

Hung Chang. The public came to see her as their ruler, even though she was

acting as regent for the actual ruler, the Emperor.

|

| Kuang Hsu aka. Guangxu Emperor |

|

| PuYi aka. Xuantong Emperor |

By the time of her death in 1908, Tzu Hsi had named the child Puyi, son of Prince Chun as Xuantong Emperor, and the last emperor of imperial China. At the end, public opinion in the west had changed somewhat. The Chinese subjects of the Manchus were calling her “Old Buddha,” and looked upon her as their ruler. During the last decade of her life, Tzu Hsi had done her utmost to change the miserable image she had been given by western reporters around 1900. Nevertheless, it is only in our time that the truth of her life and times has been told with any accuracy. The real story is every bit as thrilling and dramatic as the sordid tales of yesteryear. The Dowager Empress of China has become an icon for all time to come.

For more information see the Chinese Group on our website - Gallery of Historical Figures.

Comments